Surprise Agave Spike

March 14, 2009

One of the agaves in our yard has begun to send up a flowerstalk. I had expected this plant to grow much larger and live for several more years, but the high elevation and relatively harsh environment may have triggered an early bloom. This is Agave colorata, native to the Pacific coast of Mexico but widely planted as an ornamental in Tucson. Clusters of four-foot plants are commonly seen in gardens. It doesn’t grow as large as the immense gray Agave americana, but it’s still an imposing plant. The lovely banded blue-green leaves have prominent teeth and a long dark spike at the tip. Wild plants are reported to flower after 15 years, but cultivated plants are more variable, and the age at which they bloom depends on elevation, local microclimate, and whether or not they receive supplemental irrigation. I have ten agave species in my yard and water some of the plants occasionally, but not this species, since it rots too easily.

Agave colorata

Here’s the spiking plant in my yard with boulders and native southern Arizona oaks (Quercus oblongifolia, Mexican Blue Oak, and Quercus hypoleucoides, Silverleaf Oak). Note the cluster of small agaves at center left, behind the large plant. That’s another A. colorata that I put in at the same time, in 2002. Both plants were nearly identical and about six inches tall, but one of them grew larger and had a few offsets (young rosettes), and the other stayed small and produces dozens of short-lived offsets each year.

Like all agaves, this one will die shortly after it flowers, but the offsets will survive and continue to grow. Meanwhile, it will be fun to watch the beautiful spike develop and flower – the ultimate Ace of Wands!

Agaves are native to Mexico, central America, and the southwestern U.S. They are NOT cacti. They are closely related to the lily family and to similar large desert succulents such as yucca, nolina, and sotol. The best guidebook to this large and complex genus is the classic Agaves of Continental North America by Howard Scott Gentry (1982, University of Arizona Press, 670 pages). It has descriptions, photos, drawings, and range maps for all species, as well as taxonomic keys and plenty of background information on genetics, ecology, economic uses, ethnobotany, and many other interesting details. Unlike many field guides and botanical manuals, it’s a very readable book. It was written with a genuine love of the plants and an appreciation for the land in which they grow.

Nature Book Review #5: A Cactus Odyssey

January 6, 2009

Fifth in an occasional series of natural history book reviews. I choose special favorites that I own and use regularly, but they might not be readily available in your local bookstore or library. Books reviewed here can be purchased through Amazon.com by following the links from my Southern Arizona Desert Botany homepage.

A Cactus Odyssey: Journeys in the Wilds of Bolivia, Peru, and Argentina. By James D. Mauseth, Roberto Kiesling, and Carlos Ostolaza. 2002, Timber Press, 306 pages, hardbound.

A Cactus Odyssey

For people who are still contemplating several weeks or months of cold, wet weather, this book is a cheerful winter reading selection. It’s an informal, non-technical, and entertaining natural history travelogue written by three botanists who journeyed throughout South America to study cacti. Most of the cacti and other plants in this region are poorly known, and some have been so little studied that they do not even have well-established scientific names. This book is packed with beautiful photos of spectacular and often bizarre cacti, and is full of interesting scientific tidbits and thought-provoking speculations that will inspire any naturalist. The authors present fascinating details about the flowers and growth habit of many species, and explore questions of habitat, distribution, and evolution. They do not just present disconnected facts, but communicate their curiosity and deep respect for their chosen field of study and for the land through which they travel. If you are already a cactus expert, this account will renew your appreciation for one of the most distinctive families of New World plants. If you aren’t botanically inclined and your interest in nature is more general, this book will awaken your sense of wonder at the diversity and tenacity of life.

Nature Book Review #4: Lichens of North America

December 29, 2008

Fourth in an occasional series of natural history book reviews. Books reviewed here can be purchased through Amazon.com by following the links from my Southern Arizona Desert Botany homepage.

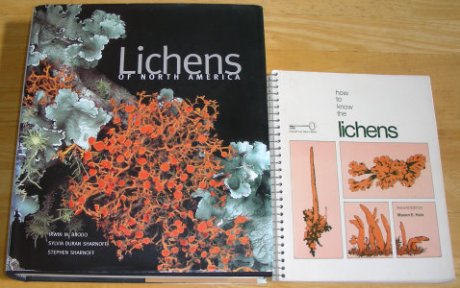

LICHENS OF NORTH AMERICA, by Irwin M. Brodo, Sylvia Duran Sharnoff, and Stephen Sharnoff. 2001, Yale University Press, 828 pages, hardbound.

This is certainly one of the most beautiful and ambitious natural history books ever published. Printed on smooth, sturdy paper and lavishly illustrated with hundreds of stunning photos, the “Big Book” is an important addition to any naturalist’s library. It contains keys, descriptions, and spectacular photos for about a third of U.S. lichen species. The introductory material stands alone as a significant up-to-date work on lichen natural history, and includes detailed background information on lichen biology, chemistry, ecology, and a fascinating and useful section on geographic distribution. The text is carefully prepared, well organized, and very readable. It is designed to reach the broadest possible audience, from professional scientists to beginning naturalists, and succeeds very well. This is a wonderful browsing book for the armchair naturalist, a useful and informative guide for lichen enthusiasts of all levels, and an inspiration for nature photographers.

The book is dedicated to the late Mason E. Hale, the American lichenologist who wrote How to Know the Lichens, which was the first detailed guide to American lichens that was written for the general public. Dr. Hale bought and autographed a copy for me in 1984, when I worked for a summer as his intern at the Smithsonian Institution’s Botany Department. It’s a spiralbound paperback, filled with meticulously detailed keys and descriptions, and illustrated with very high quality black and white photos and line drawings. Despite the huge difference in size, Lichens of North America borrows several design elements from its predecessor, including the square page format, the colors used for the cover art, and the font style used for the title – a respectful yet whimsical touch. For comparison, both books are shown in the photo.

Lichen Books

A photo gallery and other information is available at the book’s website:

Nature Book Review #3: Little Big Bend

November 3, 2008

Third in an occasional series of natural history book reviews. Books reviewed here can be purchased through Amazon.com by following the links from my Southern Arizona Desert Botany homepage.

A few weeks ago, a Texas naturalist named Roy Morey sent me a fern photo for ID confirmation. Out of the blue, I received this gift – a picture of rare Notholaena greggii, a Mexican xerophytic fern that enters the U.S. only in the Big Bend region. It makes a lovely addition to my online guide to desert ferns:

http://www.mineralarts.com/ferns/ferns/Notholaena_greggii.jpg

The agave-like leaves in the photo are Hechtia texensis, which looks like a lechugilla but is actually a bromeliad – and a sure indicator that you’re looking at a plant from Big Bend, not Arizona! I was delighted. In addition to its spectacular scenery, Big Bend National Park is famous among botanists for its plant diversity. I have never been there, but for years we have been hoping to take a vacation there to look for some of the rare endemic ferns, small cacti, and shrubs. A few days after he sent the photo, Mr. Morey sent me a copy of his book, LITTLE BIG BEND, which is reviewed below.

Little Big Bend: Common, Uncommon, and Rare Plants of Big Bend National Park. Roy Morey, 2008. Published by Texas Tech University Press, 329 p.

There are several regional field guides available for plants of the Big Bend region. This one is a bit different from others. It’s a sturdy, glossy, 7.5″x10″ paperback, too large to fit in a backpack but just right to keep at camp, in the car, or to study at home. This format showcases the beautifully crisp photos, printed much larger than in most guides, so the tiny details are easy to see and admire. Each plant is given a page for one or more photos and a detailed description which is non-technical and very readable. The book includes annual and perennial wildflowers (many of which are either rare or have rarely been photographed), a few trees and shrubs, and even two ferns (Pellaea ternifolia and P. intermedia, both of which are also found in Arizona). This is not a comprehensive regional guide, but an introduction to some of the plants that are less common, inconspicuous, or just overlooked. Some are endemics whose range is limited to the park itself, some are found throughout the Trans-Pecos region, and a few have wider distribution in the Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and even Mojave deserts. For me it was especially interesting to compare Texas species of genera that have similar representatives in the Arizona deserts. My only complaint about this book is that the color in many photos is slightly oversaturated, and in bluish or purple flowers it is shifted too far towards the red end of the spectrum. This appears to be a problem with the printing process rather than the original photos. But the photos are spectactular, and the lighting and contrast are especially well done.

The book also includes a brief illustrated overview of Big Bend National Park and its natural history, specific locations and conservation status for selected plants, a checklist, glossary, and list of references, photography details, and other interesting information. Technical data (authors of species, classification problems, etc.) is kept to a minimum, so the species discussions are informative but not cluttered. The result is an impressive book that carries on the 19th century “gentleman naturalist” tradition of scholarship, enthusiasm, beauty, and meticulous accuracy in illustration.

Nature Book Review #2: The Jepson Desert Manual

May 11, 2008

Second in an occasional series of natural history book reviews. Books reviewed here can be purchased through Amazon.com by following the links from my Southern Arizona Desert Botany homepage.

The Jepson Desert Manual: Vascular Plants of Southeastern California. Bruce G. Baldwin, et. al, editors. 2002, University of California Press, 624 pages, softbound.

I bought this book at the Joshua Tree National Park visitor center. It was the height of spring wildflower season and I was looking forward to meeting many new Mojave Desert plants. I already had California Desert Wildflowers by Philip A. Munz (1962, University of California Press, 122 pages, paperbound). It’s a very nice and useful book, but I was hoping to find something more complete. Good botany books are difficult to find in the West.

I was delighted with The Jepson Desert Manual. It is an interesting hybrid between a traditional botanical manual and a field guide. It has the structure, language, and completeness of a formal botany, but descriptions are abbreviated and illustrations are stripped down to the bare essentials, creating a book that is easy to use in the field. Unlike most popular guides, it includes ferns and grasses as well as trees, shrubs, and wildflowers. This book is ideal for someone who has never used a botanical manual or has tried and found them frustrating. Technical terms are limited to the most useful descriptive words, all of which are clearly defined in an excellent illustrated glossary. A geographic discussion and detailed maps are very useful, especially for those who are unfamiliar with California. Following a hundred-year tradition in natural history guidebooks (including the Munz guide that is this book’s ancestor), there is a central section with color plates. The photos are of very high quality, and illustrate many of the most distinctive Mojave Desert wildflowers.

For each genus, there is a general description, a brief diagnostic key, individual species descriptions, and line drawings of one or more species. The diagnostic keys are independent of the descriptions, so they can be used or ignored as desired. Descriptions are quite abbreviated but do contain specific measurements, fruit characteristics, details on distribution and habitat, and other facts that are usually missing from popular guides. My only criticism is that I would have preferred to have line illustrations for ALL plants in the book, especially in large genera with many similar species. I don’t think this would have added many pages, especially if superfluous items were omitted (such the horticultural section, which is too generalized to be useful, and the extensive and pompous documentation on the book’s history and structure.) The binding is fragile for a large paperback, especially for the heavy use that this one is likely to get from many readers, but it does keep the price affordable. Overall, this is a wonderful book for botanists, land managers, serious naturalists, and California desert hikers who want something more complete and informative than most wildflower guides. It’s also a good introduction to technical botanical manuals, encouraging the transition from “picture matching” to more formal taxonomic study. It is a joy to use and offers a treasure trove of lore and images for this unique desert region.

Nature Book Review #1: The Great Cacti

May 1, 2008

First in an occasional series of natural history book reviews. Books reviewed here can be purchased through Amazon.com by following the links from my Southern Arizona Desert Botany homepage.

THE GREAT CACTI: ETHNOBOTANY AND BIOGEOGRAPHY, by David Yetman, 2007. University of Arizona Press, 297 pages, hardbound.

This beautiful book contains photos and descriptions of more than 100 species of giant columnar cacti in North, Central, and South America. As the title says, it includes detailed distribution maps and plenty of details on current and historical indigenous use of each species. But it is most valuable for its photos and natural history discussions, for which it is the only widely available comprehensive resource on these cacti. The United States is home to only three giant cacti: the senita and organ pipe (both almost entirely restricted to Organ Pipe Cactus National Park) and the saguaro (southern Arizona and extreme SE California). Americans who have cactus gardens or who vacation in Mexico may be familiar with a handful of others. But this book records all the columnar cacti (many of which are rare, localized, and poorly known) and is a celebration of their beauty and diversity.

Each genus has a brief botanical discussion, followed by a description of each species, including growth form, preferred habitat, and any uses that local and/or indigenous people have found for it (many species produce edible fruit and usable lumber). There are photos of most species growing in their natural habitat, fruit (especially if it is gathered for food or sold in markets) and many unusually large individuals, protected or cultivated stands of cacti, and buildings or furniture made from cactus wood. The writing style is accessible and informal, which means that anyone – regardless of scientific or natural history background – can enjoy and learn from this book. As a naturalist, I would have preferred more specific botanical details and technical drawings for each species, and a more concise and uniform presentation of ethnobotanical information (these paragraphs are informative, but tend to be rambling and opinionated). Oddly and unfortunately, the book’s treatment of the saguaro is perfunctory and incomplete. Far more information is available on this cactus than on any of the others, and I think the author missed a great opportunity to use this familiar icon as a significant educational “ambassador” for the other giant cacti. Despite its shortcomings (which may reflect the publisher’s preferences rather than those of the author), THE GREAT CACTI is lovely and inspiring, and a valuable gem among desert natural history books.